My book report: Have we been here before?

Stephen J. Whitfield, The Culture of the Cold War, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991

I have always had a bad habit of buying more books than I have time to read. Some of them languish in boxes for years until I come across one that has been waiting patiently for the right moment. Who's this?

"He scraped the raw nerve of the nation's anxiety and turned it into a neurosis. He spit in the eye of constituted authority, undermined public confidence in the government and its leaders, and tore at the nation's foreign policy with the indiscriminate ferocity of a bulldozer. He used lies, slander and innuendo to smash his opponents and to build his own image of invincibility..."

Chills, right? That was a New York Times reporter named Cabell Phillips writing in 1954 about Joe McCarthy, freshly censored by the Senate but far from de-clawed. He gave his name to an era and to the practice of substituting emotion for reason and accusation for facts. Remind you of anyone?

We haven't been in 2025's sort of existential crisis, of course, but close, in the Civil War and again in the Cold War. With no threat of invasion or dissolution, with a crackling postwar economy and the dizzying growth of the middle class, the suburbs, the universities and scientific advances like polio vaccine and jet travel, the most powerful country on earth chose to lose its mind over phantom menaces. It's not as if the Soviet Union and China weren't doing terrible things to their own people and to those of East Germany and Hungary and Korea, but they weren't interfering in our elections or corrupting our government. For reasons of their own certain people -- all right, Republicans long locked out of power -- decided to act as if they were.

Whitfield starts with the political culture of the immediate postwar period and traces the spread of suspicion, paranoia and conformism into journalism, religion, film, television and education, starting with the use of Congressional committees to identify and vilify dissenters. Above it all towers the adored figure of Dwight Eisenhower, war hero and political outsider who was far from the benign granddad we now remember. He contemplated stripping "communists" of citizenship and regretted appointing Earl Warren to the Supreme Court after Brown. I use quotation marks because words like "communist" and "Marxist" were applied randomly to anyone the speaker disagreed with, much like today. ("When Truman proposed a plan of national health insurance in his State of the Union address in 1948, the American Medical Association bitterly attacked it, warning that 'a monstrosity of Bolshevik bureaucracy' would result." We don't hear much about Bolshevism anymore.) "[Ike's] first Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, a millionaire named Oveta Culp Hobby, objected strongly to the free distribution of the polio vaccine that Dr. Jonas Salk had developed for children, and which the government declared safe in 1955." The wars go on.

Today the Alien Enemies Act is abused; in 1949 it was the Smith Act which, as Whitfield says, "made words treasonable." Eleven officials of the US Communist Party were convicted of conspiring to overthrow the government and their lawyers were jailed for contempt of court. Free speech and its defense were to be shut down together. Message received?

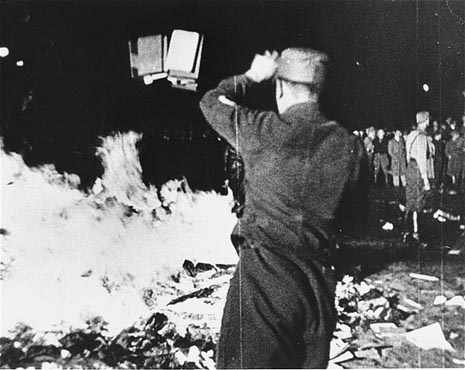

Everything else we have become numbingly familiar with seems to have its roots here. Civil rights? "Woke" was mild compared to what its advocates were accused of. Purging libraries? Sorry, Moms for Liberty, Roy Cohn and G. David Schine were there ahead of you. Scripted "reality shows" like The Apprentice? The rigged quiz shows did it better. Megachurches would not exist without the enormous revivals of Billy Graham, who brought Aimee McPherson and Billy Sunday into the television age.Whitfield is especially insightful about television which, unlike radio and movies, appeared during the Cold War and was programmed, so to speak, not to rock the boat. Good Night, and Good Luck is currently playing to crowded houses on Broadway; some people may not like to be told that numerous other media went after McCarthy first: "Except for a four-minute segment a month after See It Now [the precursor to 60 Minutes] began, Murrow and [producer Fred] Friendly did not tackle McCarthy directly until the spring of 1954, having ducked opportunities to do so for well over two years." But when they did, William Paley and CBS did not abandon them, so that's something. Still, liberal voices in television remained rare and embattled, often to our detriment: "An audience that got the impression that a secretary of state's pronouncements were sacrosanct, that had rarely been challenged by a wide diversity of opinion, and that confused credulousness with patriotism was easily misled as the disastrous involvement in Vietnam deepened. Though democratic institutions were supposed to require an informed citizenry, the torpor of television programming had helped atrophy whatever mental habits of skepticism and independence the mass audience might have cultivated."

Whitfield devotes space to cultural milestones of the era like Dr. Strangelove, Catch-22, My Son John, High Noon, The Quiet American, Chaplin's little-seen A King in New York, and the literary output of Mickey Spillane and Ayn Rand; periodically he reminds us that the madness that cost Americans livelihoods, freedom and friends does not compare to what was happening in the Communist world, where people died by the millions for lesser or no transgressions. Nevertheless it's a sad, sometimes angry book because it is a chronicle of wasted talent and wasted time. The junior senator from Wisconsin and his cohort did so much damage -- imagine if one of them had become president.

Comments

Post a Comment