War and crime

How do you distinguish the wars from the war crimes? What we consider crime -- the wholesale slaughter of civilian populations -- is as old as war. The ancient world expected cities like Carthage to be vaporized, to employ a modern word, by the vengeful victors -- old people killed, women and children enslaved, nothing but empty ruins left to crumble under the North African sun. Probably more Carthaginians died at home than fighting the Roman legions, with the same pattern repeated countless times from China to Britain. The oldest western epic the Iliad opens with a squabble over an enslaved girl and ends just before the destruction of Troy.

It was not until the twentieth century that anyone began to consider war on non-combatants to be a crime. The best estimate of the 1914-1918 war is that more civilians (ten million) than military (9.7 million) died, many of them victims of the great pandemic known as "Spanish flu." The Red Cross and the first Geneva Convention date from the 1860s but only in 1949 was there an accord among nations for the treatment of civilians. Now there was a term for what happened to Carthage: war crime. We haven't ended it but at least we know what to call it.

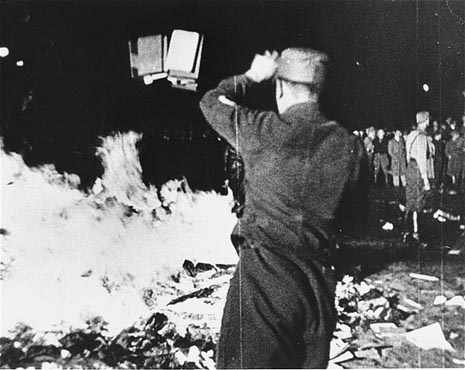

If there is one thing our modern wars have in common it's the mass grave. In the distant past mass graves were of necessity dug for victims of plague and other diseases. Now they almost always signal that someone is trying to cover up an evil act and avoid exposure and the world's disapproval. World War II was both an ancient and a modern war, with millions murdered and enslaved and rape on a mass scale, but also serious attempts to conceal war crimes through cremation and burial. No one was supposed to discover the bodies of Polish POWs in the Katyn Forest, and when the Germans did, the Soviets acted surprised. No one was supposed to know how many Jews and other civilians were shot, starved and gassed, but the German habit of careful record-keeping betrayed them, and in the final weeks there were too many corpses to hide.

At Nuremberg the Allies made it clear that the rules of warfare would have to be seen to be enforced. To make it clearer, some Germans were hanged. Point made, right? Well, not really. Here we are in the third decade of the twenty-first century and war is dirtier than ever. Outside Belgrade in Batajnica the mass graves of Kosovar Albanians were discovered in 2001 and others are still being found. Thirty years after the genocide, mass graves are uncovered in Rwanda. Two years after the invasion Ukraine is full of mass graves, some showing signs of torture (Izium, Bucha. Mariupol, every place Russians have been, it seems).

Nevertheless it's sickening to read about mass graves at two hospitals in Gaza, 283 bodies at Nasser Hospital, another 30 at al-Shifa. According to the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights some were old people and wounded who presumably died when the hospitals were shelled. Others, however, were naked with their hands tied. The Israel Defense Force acts surprised. Bombing hospitals, a bullet in the neck Stalin-style -- does it really matter? This is our staunch democratic ally, the only power in the region we can rely on. This is us.

Coincidentally Robert Reich has just published "Protesting against slaughter isn't antisemitism," as students at American universities are arrested and suspended for doing exactly that. Bernie Sanders on the Senate floor calls for $8.9 billion in "unfettered offensive military aid" to be stripped out of the Israel aid bill. First we lose our right freely to assemble, then we lose -- what? Our humanity? I can't believe Americans who gathered last night to celebrate the end of their ancestral enslavement in Egypt want this to continue in their name.

Comments

Post a Comment